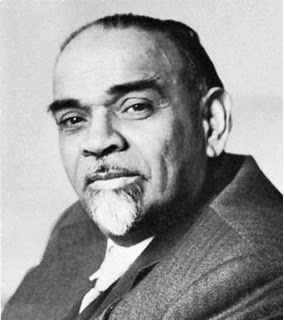

Sardar K. M. Panikker – A Life Sketch

Falling in with own ethics, and fights unafraid

In the life’s battles, attains the tranquil state.

This is the philosophy of life Sardar K. M. Panikker introduced through his thought provoking lines of his beautiful poem Chinthatharangini (the river of thoughts). A genius with command over a wide spectrum of subjects ranging from literature to administration, which he embellished in the most accomplished manner, Panikker was a rare Indian who carved a niche for himself among the international community of scholarship, a fete few Indians could achieve.

He was born on 13 May 1894 into the aristocratic Chalayil family of Kavalam at Kuttanad, the place popularized as ‘Kottonora’ by the anonymous author of the Roman travelogue, Periplus of the Eritrean Sea. Kuttanad with its infinite water sheet interspersed with betel groves, bee-loved coconut glades, meadows and seductive chartreuse of the rice paddies, developed a cosmopolitan culture. Its lakes and lagoons offered much to the weary and studious travelers hailing from far of lands. The far famed rice bowl of Kerala, Kuttanad was in those modern days the hub of international commerce and contacts that developed a cosmopolitan culture. Definitely it is no surprise that it had later given birth to such an internationally reputed genius as Sardar Kavalam Madhava Panikker.

Initiated into the three R’s at the very young age of four, Madhavan, as he was fondly called, quickly swallowed algebra and the Malayalam literature, Srikrishnacharitham manipravalam. He underwent prodigious schooling at Maharaja’s School, Thiruvananthapuram, the school at Anaprampal near Thalavady (Alappuzha District) and CMS School at kottayam. Later, having had his Matriculation passed from St. Paul’s High School, Madras, Madhavan took to his higher education at Madras Christian College. Later he left for London where he joined the Christ Church, Oxford for higher education.

He was good at English education and a promising student of History, the twin merits that helped him scale unimaginable heights both in life as well as academic career. But he was not so mad after these faculties as to forget his native land and mother tongue. In fact the new experiences he gathered from his London life coloured his imaginations and enriched his academic excellence so much so that he could write brilliantly about Oxford, its scholastic accomplishments and many a burning question of the time in the leading Malayalam publications like Bhashaposhini, Kairali, Mangalodayam, etc. Like the Savyasachi who darted with both hands he handled very sublime and beautiful Malayalam, both prose and poetry, with as much ease as he wrote English. His Bhupasandesham, Sandhyatharam, Haidernaikker, Amruthalahari, Swathanthryasamaram, Rasikarasayanam (translation of Omar Khayam’s Rubayyath), Pankiparinayam etc., still remain the gems of Malayalam literature.Â

His maiden writing in English was the article on freedom movement in Hungary carried by the Indian Review of Madras published by G. Natesan. And the writer in Panikker received further exposure when he was selected first by Dr. Sir. C. P. Ramaswami Iyer in the essay competition conducted in English for the Indian students in foreign countries by T. K. Swaminathan, the Editor of Colonial Review. The publication of this essay headlined ‘Introduction to the Problems of Greater India’ (1916) with a foreword by Sir. C. P, inspired Panikker to write more. And with his brilliant write-ups, which appeared in Modern Review, Hindusthan Review, Indian Review, Common wheel, etc., getting the attention of academics and intellectuals he started scaling further heights.

History and philosophy he juggled with utmost ease. In fact like all the great visionaries Panikker too looked to history as the passage to Philosophy. History has a meaning, a sense, and a message to impart to humanity, a message that would help it attain cultural progress. He much loved the spiritual values upheld by his motherland, India and her Oriental neighbours and equally tiraded against the western vested interest, which by exploiting the Asiatic countries tried to feather its nests. With extraordinary ability he exposed before the intellectual community the devilish means the Occidental forces followed in their exploitation of the Orient. Though he topped in command over English language and literature, Panikker didn’t parrot the western culture as many others did. This is well reflected in all his writings which bristle with adoration to the ancient heritage his motherland nourished down the millennia. Capable to fan the flames of patriotism, they instill love of Indian culture and heritage in any student of history. His criticisms of the western distortions in Indian history written in conformity with the European colonial requirements apart, he darted aptly strong and piercing replies too to many of the historical confusions such distortions have brought about. His A Survey of Indian History abounds in such replies, which do away many misunderstandings born of European Indology. A book the students of Indian history and culture must compulsorily read, it is one of the classics of history. It strongly comes out against the European disintegrating tendency to put the Indian society and minds at sixes and sevens. While all studies aimed to create coherence of thought and action out of de-coherence, leading towards the ultimate unity of all, the method the Europeans followed in writing Indian history was aimed at creating de-coherence, disintegration and discord. Europeans applied this de-cohering technique in all the possible contexts of Indian history to present India as an ideologically and culturally divided house. It is interesting to look at how Panikker responds in such contexts of British writings on Indian history. For instance he exposes the European writers’ deliberate depiction of Emperor Asoka as the Buddhist Constantine and the fallacy of looking at Indian history through European spectacles. Panikker deals with this travesty of truth thus:

Asoka is spoken of as a Buddhist emperor and his reign as a kind of Buddhist period in Indian history. The distinction between Hinduism and Buddhism in India was purely sectarian and never more than the difference between Saivism and Vaishnavism. The exclusiveness of religious doctrines is a Semitic conception, which was unknown to India for a long time. The Buddha himself was looked upon in his lifetime and afterwards as a Hindu saint and avatar and his followers were but another sect in the great Aryan tradition. Asoka was a Buddhist in the same way Harsha was a Buddhist, or Kumarapala was a Jain. But in the view of the people of the day, he was a Hindu monarch following one of the recognized sects. His own inscriptions bear ample witness to this fact. While his doctrines follow the middle path, his gifts are to the Brahmins, Sramanas (Buddhist priests) and others equally. [It is also to be noticed that the Madhyamikamarga or the middle path the Buddha prescribed for his followers was nothing new to Indian tradition. Vairagya that lies between Kama and Krodha had already been with the Indian thought. Sri Krishna in the Githa had already dealt with the reactionary chain of vishayasanga, Kama, Krodha, sammoha, smruthivibhrama and the ultimate destruction at length.] His own name of adoption is Devanam Priya, the beloved of the gods. Which gods? Surely the gods of the Aryan religion. Buddhism had no gods of its own. The idea that Asoka was a kind of Buddhist Constantine declaring himself against paganism is a complete misreading of Indian conditions through the eyes of the Christian Europe. Asoka was essentially a Hindu, as indeed was the founder of the sect to which he belonged. (A Survey of Indian History, Asia Publishing House, Mumbai, 1977, pp. 33-34)

Panikker sharply reacted to the witch-dance of the religious fundamentalism and fanaticism sworn to damage, destroy and devastate India and its culture down the centuries. The fanatical powers, which tortured the native people to build the theocratic empires in India, did not get an easy go from Panikker’s criticizing quill. And definitely it was Aurangzeb, the bigoted Calvin of Muslim India who was much vilified and pooh-poohed by Panikker. Though Aurangzeb entrusted his most eminent officer to “watch that son of a dog (Sivaji)†and spent most of his life to contain the tide cultural nationalism under Sivaji, it all ended in vain and he died a defeated man. The Sardar satirically comments thus:

He [Aurangzeb] died a defeated man, but he died for an ideal – the unification of India. He was in fact the martyr for India’s unity, but the unity he desired to establish and for which he ruined his great inheritance was not the unity of a national state… but of an Islamic state – the rule of a conquering minority over India. It is that ideal which lies buried under the mausoleum at Aurangabadâ€. (A Survey of Indian History, p. 181)

Panikker took up the moral commitment to expose how fanatical the Western forces were in their approach to other oriental cultures also. It is interesting to note that the European Church with all its operations falling wide off the real teachings of Jesus Christ was the best example of colonial and imperialist interests of the European powers and it was up to any extent ready to prostitute the ideals of the great Nazarene if that would help exploit and destroy the cradles of ancient civilization to feather its nest. And it had an army of missionaries to execute its greedy warrant. Oriental cultures like India, China and Japan suffered a lot from them. Most notorious was Francis Xavier who was sworn to uproot the Oriental cultures by torpedoing their socio-economic stability and bring them under the European domination. For this he and his coterie were prepared to adopt any devilish means. Thus Panikker says:

In 1543 Goa was made a Bishopric with authority extending over the entire Far East. Special instructions were issued to the Portuguese Viceroy to root out the infidels. Hindu temples in Goa were destroyed and their property distributed to religious orders (like the Franciscans) in 1540. (Asia and Western Dominance, Somayya Publications, Mumbai, 1999, p. 280)Â Â Â

He further writes:

The Portuguese came to India with a Cross in the one hand and a sword in the other. King Joao 111 (1557-1578) was particularly anxious about the spread of Christianity and wrote to the Viceroy Joao de Castro demanding that all power of the Portuguese should be directed to this purpose. “The great concernment which lies upon Christian princes to look to matters of Faith and to employ their forces for its preservation makes me advise you how sensible I am that not only in many parts of India under our subjection but in our city of Goa, idols are worshipped, places in which our Faith may be more reasonably expected to flourish; and being well informed with how much liberty they celebrated heathenish festivals WE command you to discover by diligent officers all the idols and to demolish and break them up in pieces where they are found, proclaiming severe punishments against anyone who shall dare to work, cast, make in sculpture, engrave, paint or bring to light any figure of an idol in metal, brass, wood, plaster or any other matter, or bring them from other places; and against who publicly or privately celebrated any of their sports, keep by them any heathenish frankincense or assist and hide the Brahmins, the sworn enemies of the Christian profession- –.It is our pleasure that you punish them with the severity of the Law without admitting any appeal or dispensation in the least”. (K M Panikker, Malabar and the Portuguese, Voice of India, New Delhi, 1977.)Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â

Â

Panikker’s statement that these missionaries were iconoclasts number one is testified to by their own writings. Let us see how Francis Xavier found himself ecstatic at the images and idols of the Hindu gods being broken to pieces. Xavier writes:

Following the baptism, the new Christians return to their homes and come back with their wives and families to be in their turn also prepared for baptism. After all have been baptized, I order that everywhere the temples of the false gods be pulled down and all idols be broken. I know not how to describe in words the joy I feel before this spectacle of pulling down and destroying the Idols by the very people who formerly worshipped them. (Letter dated 8 February 1545. See H. J. Colridge, Life and Letters of Francis Xavier, London, 1861, Vol. I, p. 10)

Panikker amply exposes what these missionaries did in China for mass conversion. Here too they followed the path of double-dealings, bad manners and treachery. Their fanaticism had crossed all limits of human standards in their bid to westernize China and her traditions. Thus he writes:

On the site of the temple in Tientsin, which was also an imperial palace, the French, without any legal title, erected a Roman Catholic Cathedral in 1869…At Tienstin was also established an orphanage by a Catholic Sisterhood. These sisters arranged for the payment of a sum for every child brought to the orphanage, that is in plain words established a kind of purchase system encouraging the less scrupulous Chinese middlemen to kidnap children. (Asia and Western Dominance, p. 138)

Their creating dissention within the countries with lofty national cultures by exploiting the seeming differences among the national communities constitutes the stories of craft and cunningness. Ricci, the Italian Jesuit who reached the Chinese capital, Peking was crafty enough to saw the seeds of dissention in Chinese society.

Thus writes Panikker:

Early in his Chinese studies Ricci had detected the conflict between Buddhism and Confucianism. Realizing that the greatest obstacle to Christianity was Buddhism, he sided with Confucians and attacked the Buddhists. He quoted from the Confucian texts in support of the Christian doctrines and tried to show that Confucian doctrines did not conflict with Christianity. (Asia and Western Dominance. P. 283)

India’s case was more deplorable than that of China and Japan. While other Asiatic nations strongly responded to the fanatical aggression of the Western missionaries, Indian response in this regard was fraught with meekness and submission. This crass laxity and indifference with which the Hindus have been succumbing to such destructive forces down the centuries finally helped the alien forces uproot the very culture of India, Panikker would often point out. Differences and disagreements based on castes and communities added to this national handicap, which deterred the nation from getting united. Panikker firmly opined that it was this social inequality with no spiritual or scriptural imprimatur that helped the alien forces to drive wedges into the available differences to destroy India and its culture. Through out his writings on Indian history and culture Panikker strove to remind the Indians of their cultural coherence and strength. Indeed Panikker was one among a few concerned of the vicious problems that have been putting India and its society at crossroads.

Yet another masterpiece of Panikker that wax eloquent on the cultural heritage of India is his Studies in Indian History, which elaborately analyses India’s cultural expansion and the East-West cultural contact in ancient times. This work, which could rightly be hailed one of the classics of history and philosophy, is noted for its lofty vision. The success of life in ancient India depended on how its people balanced their spiritual and material pursuits. Panikker lucidly and philosophically explains this in one of its essays. This essay headlined ‘An Introduction to Vatsyayana’ is one of a few ennobling emendations ever written for the sutra of Vatsyayana. In it Panikker describes how ancient India balanced its approach to eroticism setting it against the wider canvas of the life’s entirety. A doyen among historians, he was a prolific writer. And all his works like Hindu Society at Crossroads, Sri Harsha

f Kanauj, India and China, India and Indian Ocean, In Two Chinas, History of Kerala, Malabar and the Dutch, Malabar and the Portuguese, to quote a few, are the ripe fruits of historical knowledge. His valuable contributions to Bharathiya Vidya Bhavan’s History and Culture of the Indian People are really a genius’ reflections on the versatility of India’s history and culture.

No wonder Panikker was crowned with many recognitions, which few could match. He was member of the National Academy of Letters (later Kendra Sahithya Academy) and Chairman of Kerala Academy of Letters. He was Chairman of the UNESCO’s advisory committee to write on the cultural values of East and West and one among the three Editors appointed by the UN for its project of writing the History of Mankind. All these missions Panikker fulfilled with admirable scholarship and perfection. The History of Mankind he wrote along with Caroline Ware and J. M. Romain still continues to dominate the scholar world. An academic to the core, a renowned diplomat, top ranking statesman with unimaginable credentials and intellectual capabilities, he was an incomparable phenomenon of the 20th century whose stature is far beyond the present day comprehension. So much was this man who dominated all the worlds he lived.

•   Author is Associate Professor of History, Sanatana Dharma College, Alappuzha.

Welcome to Haindava Keralam! Register for Free or Login as a privileged HK member to enjoy auto-approval of your comments and to receive periodic updates.

Latest Articles from Kerala Focus

- തിരുവാഭരണ പാതയിൽ സ്ഫോടക വസ്തുക്കൾ കണ്ടെത്തിയത് അന്വേഷിക്കണം: കെ.സുരേന്ദ്രൻ

- A Day with Hrudaya & Bhagya, Daughters of Veerbalidani Renjith

- സഞ്ജിതിന്റെ ഭാര്യയുടെ ജീവന് ഭീഷണിയുണ്ട്: പോലീസ് സംരക്ഷണം നൽകണം: കുമ്മനം രാജശേഖരൻ

- Kerala’s Saga of Tackling Political Violence

- Tribute to Nandu Mahadeva ; Powerhouse of Positivity

- പാലക്കാടിന്റെ സ്വന്തം മെട്രോമാൻ

- കേന്ദ്രഏജൻസികളുടെ അന്വേഷണം സംസ്ഥാന സർക്കാർ തടസപ്പെടുത്താൻ ശ്രമിക്കുന്നു: കെ.സുരേന്ദ്രൻ

- Kerala nun exposes #ChurchRapes

- Swami Chidanandapuri on “Why Hindu Need a Vote Bank?”

- Forgotten Temples Of Malappuram – Part I (Nalambalam of Ramapuram)

Responses